BUILDING COMPASSION INTO TECH

Integrating compassion with STEM

By Benny Xian — Draft v2.4

In Silicon Valley, everyone of us in tech believes we are doing good by changing the world through technology. Technologists and entrepreneurs are revered as the heroes or heroines for creating world changing ideas. In the words of Steve Jobs, “Here to the crazy ones: the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the round pigs and the square holes, the ones who see things differently. They are not fond of rules. They have no respect for the status quo. ” It is because of this very believe that created so many success stories in the valley. Behind every great success, there is a vastly different narrative. If we look back at history, both Professor Frederick Terman and William Shockley were credited with the founding of Silicon Valley. But, yet both men held a very different belief system where Professor Terman believed in giving credit while Shockley believed he had to take in order to get. Professor Terman was the Dean of Engineering at Stanford between 1944 to 1958. He believed in creating a culture of cooperation and information exchange that has since defined the region. He was known to remind others not to take credit for their success and he never once took credit for the development of Silicon Valley. Shockley was the manager of a research group at Bell Labs that received the Nobel Prize for inventing the transistor. He was furious when he learned that his name wasn’t tagged on the discovery’s patent along with John Bardeen and Walter Brattain. Eventually, Bell Labs added his name to the patent. After the initial discovery, he worked tirelessly to improve the invention further and came up with an even better transistor by himself. How come Professor Terman didn’t have to fight for any credit while Shockley had to fight hard in order to get ahead during the same time period? Which one is the correct approach to success? It turns out they both were right from their perspective depending on the world in which we live in. Doing good under Professor Terman’s world was about giving whereas doing good under Shockley’s world required taking. They both ended up with enormous success by making significant contribution to Silicon Valley and to the rest of the world. If we are doing good through different means, what is the problem?

Today, we have far more data and research available to help us understand the two very different worlds. Reid Hoffman alluded to this problem in his blog post “Why Relationships Matter: I-to-the-We”. We have essentially two very different operating systems where one is more about “I” and the other one is more about “We”. I will show you later how the Terman-Shockley narratives are related to the I vs We problem and why this isn’t necessary a problem with the technologists, but rather a fundamental problem with our operating system(s) in encouraging one system or another. In his groundbreaking book Give and Take, Wharton professor Adam Grant upended decades of conventional thinking that giving to others can lead to one’s own success. His research, based on science and data, is demonstrating that we can achieve great success like Professor Terman even under the operating system in which Shockley is accustomed to. However, I will explain why it is often difficult for someone like Shockley to understand Grant’s research despite compelling evidence. Through my intimate experience in Silicon Valley, I would like to take us on an intellectual journey into the mind of genius and how the very algorithm that propelled Silicon Valley to great success is hampering our entrepreneurial edge today. I will draw wisdom from Chip Conley, Founder of Joie de Vivre Hospitality, in applying first principle using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to help us understand our fundamental human motivation across different operating systems. Based on this analysis, it will help us to see how this can apply to the challenge of working with high achieving genius, which is the very challenge facing many tech companies including Google and Microsoft. It will get us to think harder whether genius are truly difficult to work with or whether they are being misunderstood. While we certainly know how to build high performance organizations in Silicon Valley by hiring the smartest and brightest, we are still struggling mightily to build high performance team with high trust. This is indeed a serious problem for the tech industry which is known to have the highest turnover rate of any business at 13%. With a deeper understanding of human motivation, it will help us to rethink our current approach in management and leadership in Silicon Valley. I do believe we can reconcile the two operating systems into one as Hoffman did cleverly with the equation: “I to the superscript We”. Based on research, I also believe we can collectively create a better environment where genius can thrive together for the greater good. But, this can only happen if “WE” come together.

Reid Hoffman, “Why Relationships Matter: I-to-the-We” Blog

Based on my experience as an immigrant and as a tech entrepreneur who have worked with some of the smartest in the world, my thesis for solving the I-vs-We problem in Silicon Valley is through compassion because no one has yet to show us the difference between the two operating systems and how each one affects the way we see the world. We tend to believe that: we can’t be compassionate and be competitive, we can’t be nice and be successful as fierce entrepreneurs, or we can’t get ahead by giving unselfishly. Marc Benioff, CEO of Salesforce, is known to be one of the most compassionate leaders in tech having published three books - The Business of Changing the World, Compassionate Capitalism, and Behind the Cloud - where he made countless convincing arguments on why doing good for others should be integrated together with making profits as a company. Coincidentally, the founding DNA of Salesforce was built on integrated philanthropy from day one. If Benioff is able to make it work by pushing for compassionate capitalism, isn’t it time to push for compassionate engineering and science? Why are we not talking about compassion when we talk about technology? What if we now have the knowledge to help genius like Shockley to succeed without having to fight? What if we can help engineers and scientists to achieve their goals without seemingly offensive? While we don’t necessary have all the answers, I invite you to join this important conversation. I believe this is an important time to add a “C” to STEM especially since artificial intelligence is advancing rapidly. The way we see the world is producing the very algorithm behind artificial intelligent systems and our human biases are being used as training data for these systems. Do you want our future robots to think in terms of “I” or “We”? Think again.

SEEING THROUGH THE IMMIGRANT LENS

“Fish don’t know they’re in water.”

Immigrants bring a unique perspective to Silicon Valley in addition to our brain power in solving some of the most technically challenging problems. It is this unique perspective that helps us to spot opportunities where others might not. It is also because of our experience that enables us to be comfortable with the uncomfortable. Like fish out of water, the uncomfortableness makes us keenly aware of our surrounding. Being trained in science and technology, my mind is obsessively seeking for patterns out of chaos because I feel the need to make better sense of our collective experience. One of the questions I often wonder: how do we know our view is not distorted unless we try out different lens? It turns out, as immigrants, we have an interesting vantage point given our diverse experience rising through a different socioeconomic class. As shown by decades of research at Stanford under Professor Carol Dweck, our mindset indeed determines the lens through which we see the world. When we have a growth mindset instead of a fixed mindset, we don’t see failures as failures. We see them as learning experience. Knowing this, wouldn’t it make sense for us to understand our mindset and what conditions would have direct impact? As technologists, can we engineer contact lenses with different color to help people see the world differently? Perhaps, it is time to look for answers from fundamental research.

While Terman and Shockley are busy building Silicon Valley, A.H. Maslow published one of the most important works in human history to help us rethink human motivation in 1943. While I first learned about the Maslow hierarchy of needs back in my college psychology class, it wasn’t until last year where it finally made sense for me after spending a few days with Chip Conley. It is one thing to read about the Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. It is quite another to have the experience living through different layers of the pyramid, and seeing how people behave quite differently at each level. As an immigrant from China, we grew up struggling for the basic needs as our parents worked hard to make ends meet. Just like the fish in water, I didn’t know any differently and I was just as happy living under very limited resources. But, the experience helped me to understand people living in survival. Because our parents experienced poverty and famine in the 1950s, it instilled great fear in their mind which had a lasting impact on their life, not because they are still struggling (in fact, they have achieved business success in America beyond their dreams), but because they are still living under the lens of fear. When someone is living life with fear, they tend to solve problems through fear and threats. They are very skeptical of others and their behavior tends to be hostile because they are having difficulty trusting others. While I grew up under the lens of fear, being at Stanford exposed me to a very different world with a very different language. It is where I got inspired by so many heroes and heroines, like Jensen Huang, Jerry Yang, and Andy Grove, who have achieved great success and who have given back so much to others in the community. To me, this is a better world where success doesn’t have to come from the expense of others. It is very much different from the survival mindset where people are constantly looking to take advantage of others and someone always has to lose. It is through the extreme contrast between the two worlds that makes it easier to see the difference and how we can make a conscious choice on the world we live in. As immigrants, I strongly believe we have the responsibility to help others by raising awareness on things that doesn’t make sense. This is perhaps one of the greatest gifts of being immigrants.

Understanding genius through their lens

We may never fully comprehend the deepest inner workings of genius mind. But, if we seek a better understanding of the way they think, we can work cohesively together for the greater good. In our culture, we have a tendency to view genius as separate or superior from the rest of us. I believe it is better to view them as simply different. Everyone has a different gift, and theirs happens to be technology. Being at Stanford with an acceptance rate below 5%, I was fortunate to have the experience studying alongside with the best of the best from the world. Not only is Stanford attracting the smartest in IQ, it also attracts the most competitive of all. Once you get into Stanford, you will quickly recognize genius because they are far ahead of the pack. I am referring to the top 5% of the top 5%. These are not high achievers, these are super achievers! They are the ones setting the pace and inspiring the rest of the class to push harder. This special group of people is important to understand because they are the driving force behind our future direction and our culture in tech. If it doesn’t concern you, they are building the algorithms behind artificial intelligence.

To excel in engineering and science at an early age, it requires a highly analytical mindset which also attracts certain personality traits. Many of us in tech are gifted in logic but unfortunately not as good in understanding human emotions relative to other fields. Perhaps, if we are too in tune with people and emotions at an early age, it would be difficult to get through engineering school, and the ones who do, become the leader of leaders. John Hennessy, former President of Stanford, is a great leader not only because of his contribution to computer science, but because of his genuine interest in people. John is a rarity in engineering given his understanding of both technology and people. Wouldn’t it be great if this is the norm instead of rarity? It is perhaps our analytical mindset that drives us towards certain courses in school. When you are good at something, there is a tendency of doing more of it and ignoring the rest. Once we get into engineering school, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy since we focus exclusively on developing our left brain. Without awareness and training, our right brain muscle, the emotional side, is not being developed as much. In Silicon Valley, we reinforce this predisposition when we idolize nerds like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. All the sudden, it is cool to be nerds without having to be good with people.

As technologists, we’ve loved to solve every problem known to mankind with algorithms ever since the first algorithm was written for the Bernoulli numbers in 1842. Our engineering brain is naturally wired for efficiency and we prefer a world without emotions because emotions are not easy for us to understand unless we can model it mathematically. When we do, machines will become closer to humans. And, for the tech genius in us, we are becoming more like machines devoid of human emotions. For the ones with genius mindset, human emotions are perceived as a weakness. Tim Cook understood this is becoming a real problem when he made the following statement at the 2017 MIT Commencement:

“I’m not worried about artificial intelligence giving computers the ability to think like humans. I’m more concerned about people thinking like computers without values or compassion, without concern for consequences.”

When we ignore human emotions, it might makes us very effective and highly functioning as engineers and scientists. We prefer to operate efficiently like the machine that we build - free of any irrational thinking. It is because of this extreme mindset that enables these genius to achieve amazing feats through technology. At the same time, it makes them very challenging to work with when they are so logical. For every problem, we always have a technical solution. GIT was invented to make it possible for engineers to do software development at scale without face to face interactions. It was designed very well to remove friction from human interactions. The result was phenomenal because it is the way engineers like to work. But, can we work together exclusively through GIT?

In Silicon Valley, every major tech company has a core group of genius and many ventures like Google was founded by genius. As we revere genius so much in tech, we are inadvertently promoting the genius mindset in our culture and challenging behavior often comes with it. At Transmeta, it was a very interesting experience when you bring together the smartest and highly analytical people in one building. Despite how rational we were supposed to be, we struggled to work cohesively across different departments while people are working well within their own groups. The communication between engineering and marketing was virtually non-existent because both departments have lost trust with each other. As a result, engineering was doing their thing while marketing was doing theirs. Because of my training in engineering, I was brought in to help bridge the communication between engineering, marketing, and customers as the product manager for two major product lines. Typically, only one product manager is assigned for each product. Unbeknownst to me, every single marketing person before me was rejected by the engineers because they were not respected without an engineering background. I didn’t know at the time what I was signing up for. If I knew that it would put me in direct crosshair against two very challenging engineering teams, I should have asked for a bigger paycheck to deal with combative situations that often turned hostile against marketing. Being trained in engineering with a marketing hat, I can see why these engineers couldn’t respect marketing because it is difficult for left brain dominated engineers to appreciate right brained marketers. To these engineers, marketing is trivial and secondary to engineering. Many engineers believe they can do marketing and sales if necessary, whereas they don’t think marketing people can do their jobs. Interestingly enough, similar dynamics happened between software and hardware engineering with each thinking they are superior to the others. Despite having the most talented people in the valley, we were not really working together despite our individual IQ. At the same time, hardware and software engineering still managed to create one of the engineering marvels of our time - the world’s first software based VLIW microprocessor. For decades, no one was able to rival Intel’s x86 until we showed up. Before joining Transmeta, I got invited to meet Bill Davidow, the legendary marketing chief behind the Operation Crush campaign at Intel, because he was the chairman of the startup I was working with. At that meeting, he was very curious about Transmeta and he gave me invaluable marketing advice that I would never forget. Bill, being a good friend of Andy, was concerned enough about Transmeta to check me out. If engineering is producing great output, why not continue the way we operate in Silicon Valley? Let these genius keep fighting especially since we have other problems to deal with - like sales.

Why is it so challenging to work with genius? Throughout my career, I have worked with a number of genius who are well-liked by many despite how challenging they are. When you ask people around, we know who they are. At Transmeta, Bill Rozas, our chief software architect, was perhaps the most passionate of all in engineering. His intensity in technical debates is bar none. His credential is equally impressive with a PhD in Computer Science from MIT. At the same time, he would spend time explaining complex concepts to help me understand microprocessor architecture. What set him apart from other genius who are difficult? When he debates, he wasn’t just debating to show how smart he is. He was debating for the interest of the company. For every genius like Bill, there is a genius who is challenging in a difficult way. We somehow associate genius with difficult personality. With this thinking, we don’t mind recruiting difficult talents as long as they are genius and we don’t mind contentious debate because we value constructive confrontation - a term popularized by Andy Grove at Intel. At Google, Sundar Pichai is dealing with this very issue by screening out engineers with low emotional intelligence. If we do that, wouldn’t that cross out majority of engineers from Stanford, MIT, and Caltech? We were never based on “being nice”. And, we were never given training in school on emotional intelligence. At work, we are often not given coaching until we reach senior positions. Wouldn’t it make more sense to provide training on the first day of our career? Interestingly, while Sundar is screening engineers, Larry Page is staying at the top being revered as the engineer of all engineers. Larry is known to encourage his executives to fight fiercely like him and Brin without regards to feelings. If I were an engineer at Google, I would be confused because I thought this is how we get to the top by ruthlessly out-debating, out-smarting, and outcompeting. As shown by the actions of many high-tech leaders, I believe time has changed with better understanding and there is a different way to look at the problem.

The root of our problem: our operating system(s)

When Satya Nadella became CEO of Microsoft in 2014, he inherited a company whose culture was known for hostility, infighting, and backstabbing under the leadership of Steve Ballmer. What happened to one of the greatest tech companies of our time and how come Bill let this happened? It was a powerful message that Satya gave out copies of the book, Nonviolent Communication, written by Marshall Rosenberg, at the first executive meeting. It was even more powerful that he made it known publicly! While I think the title of the book could be better, the word “nonviolent” can turn away people. The concepts are actually very useful for improving the quality of communication in any situation. Rosenberg believes the cornerstone of effective communication is empathy and compassion. Without empathy, a person is “emotionally tone deaf” as Daniel Goleman, father of emotional intelligence, puts it. Without compassion, they can understand perfectly how you think and how you feel, but they don’t care about you. Microsoft’s culture turned toxic when the hypercompetitive environment turned people against each other. It was not necessary a problem with lack of empathy. In fact, the most effective corporate climbers are the ones with very high empathy. Instead, it was more a problem of compassion.

“The human failing I would most like to correct is aggression. It may have had survival advantage in caveman days, to get more food, territory or a partner with whom to reproduce, but now it threatens to destroy us all.”

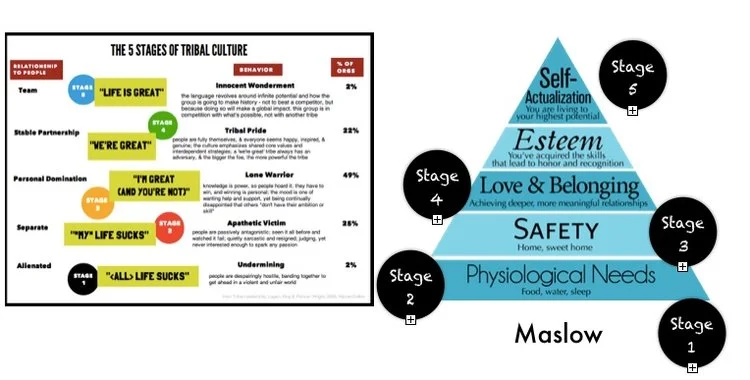

How do we, as a human race, become the way we are today? Since childhood, we strive towards individual excellence through many years of education. After graduation, we strive towards individual achievements through our career. Our educational system tends to encourage us to compete against our peers. Our society is measuring us by how many trophies we win and how many degrees we can collect from elite universities. We have been trained for many generations that winning is the ultimate goal and, oftentimes, at the expense of others. I had this eureka moment when I came across the seminal research conducted by David Logan at USC on tribal leadership. His research helps tremendously in bringing awareness to our behaviors and our language at different stages. According to Logan’s framework, there are 5 stages of tribal culture. Stage 1 and Stage 2 are people who doesn’t even have their basic needs met. These are the homeless people on the street or people living in war zones. Stage 3 is about “I” am great and you are not. Typical Stage 3 are people who constantly have the needs to one up on another. This sounds very much like the Harvard culture portrayed in the popular TV series, Suits, created by Aaron Korsh! Based on Logan’s research, good examples of Stage 3 dominated fields are legal and investment banking. When you look at legal documents, it is filled with language of stage 3 and it reflects the way we think under our legal system - you VS me instead of you AND me. It might also be the reason why many people, including investment bankers themselves, don’t like investment bankers. Stage 4 is about “we” and Stage 5 is beyond competition. If you have a stage 4 mindset, you can imagine how difficult it would be to survive in a stage 3 world. Interestingly, most of us have been trained since childhood under the mindset of Stage 3. Early on, we are encouraged to show how much smarter we are as individuals. If we listen carefully to the language of stage 3, it is mostly “I”. Coincidentally, the language of genius is consistent with the language of stage 3 whereas the language of “genius maker”, as coined by Grant, is consistent with the language of stage 4. The extreme stage 3 are the highest achievers within the group - they are simply doing what they are trained to do at its finest.

Despite good intention from leaders like Benioff and Nadella, the language of Silicon Valley is predominantly stage 3. When Silicon Valley first started, Professor Terman did not set out to build a culture of stage 3. In fact, he was known to bring talented genius together and encouraged everyone not to take credit for their success. How did we become predominantly stage 3 today in Silicon Valley? I believe the culprit: hyper-competition without being conscious and our hero-obsessed culture. Competition is good in bringing out the best in people. But, when we have over competition, it brings out the worst when everyone are competing against each other. Coupled with our hero obsessed culture of the past, we like to believe that we are the sole heroes in our success stories. When we think about Tesla, only Elon Musk comes to mind. When we think about GE, Jack Welch. Hoffman made a very good point that we still love the story of a self-made man because it is simple and easy to understand. To quote Hoffman, “Superman and His Ten Allies doesn’t quite roll off the tongue as easily as Superman.”

For many of us, we are operating under the language of stage 3 until the day we have the responsibility to lead others. This isn’t an easy transition unless we are aware of the difference between the various stages and how the metric for success is different at each stage. The very reason why we succeed by beating out many others in stage 3 is the very reason why we have trouble under stage 4. Can we be a genuine stage 4 and beyond leader after spending most of our career fighting our way up? It also explains why it is difficult for stage 4 type talents to survive under stage 3 world. As leaders, how do you protect the stage 4 talents and transform capable people beyond stage 3? Maslow might have discovered some important answers for these questions back in 1943.

First principle: understanding human motivation through Maslow

Logan’s research gives us a framework to understand tribal culture at different stages. When you map it against the Maslow hierarchy of human needs, they are surprisingly consistent. Under Maslow's theory, we cannot have safety until we have met our basic physiological needs like food, water, and sleep. And, we cannot have love & belonging until we have safety. Under the survival mindset (aka safety under Maslow), you must constantly fight other people to get what you need and you have to be constantly under guard because there is no trust between people. I understand this world very well because of my parents. For them, you are smart if you take advantage of others for personal gain. You are idiot if you don’t. In this world, nice guys/gals definitely finish last. This is similar to what we are experiencing today in Silicon Valley when we have high achieving genius competing against each other. In order to get ahead, they believe they must fight for credit. According to history, Shockley fought so hard that he ended up taking the lion’s share of the credit for the invention of transistor. Despite his subsequent effort to make corrections, his relationships with Bardeen and Brattain deteriorated beyond repair.

While we value intense competition in tech because we believe in “meritocracy”, the unintended side effect is that we start seeing everyone, including our teammates, as our competition. I think we all have stories of our colleagues being so competitive in engineering school that they wouldn’t share their notes with others. At work, we see similar behavior when coworkers wouldn’t share their knowledge because they “think” everyone is competing with them while, in reality, they are not. When they perceive everyone as competition, It becomes very difficult for them to see the contribution from others. Instead of giving credit, they end up taking credit because, for them, it is justifiable since they perceive everyone is doing it. When someone is trapped in this mindset, it is often difficult to convince them otherwise that we are all on the same team. The culture turns toxic when other team members start to behave in similar way and the downward spiral continues when it becomes a taking culture. As we become hyper-competitive in Silicon Valley, we run the risk of “disrupting” our own entrepreneurial system by the very mechanism coined by Clayton Christensen at Harvard by overshooting in IQ and undershooting in EQ. Imagine Silicon Valley with mostly lone warriors. Professor Terman himself wouldn’t have survived and there wouldn't be anyone paying it forward.

“The most meaningful way to succeed is to help other people succeed.”

Beyond survival mode, we are no longer fighting against each other but rather "for" each other. We now have the luxury to talk about love and compassion. Under this environment, trust between people is possible and people are genuinely interested in others. Silicon Valley is only possible because of many giving people who saw a need to give and help other people. In the words of Jane Stanford, co-founder of Stanford University, “to promote the public welfare by exercising an influence in behalf of humanity and civilization.” Under this environment, trust between people is possible because people are willing to invest in others for the greater good. Similarly, it was Professor Terman who encouraged and supported his students, including Hewlett and Packard, in building many great tech companies. He deliberately set up an environment where everyone of his students were helping each other. Under his leadership, he created a stage 4 tribal culture.

I am very glad that Give and Take, written by Grant, is giving us the reasons why helping others help us to succeed. However, Grant is speaking to people beyond survival stage. For people who are struggling to survive, they would not be able to understand his research because they think in a very different language. It is like speaking Chinese to a native English speaker. We need people who are well-versed in different mindsets to speak different language. Without awareness, it is the reason why it wouldn’t work to send a peacemaker with stage 4/5 mindset into a war zone to talk about compassion when everyone is fighting for survival. To be a good peacemaker, he/she needs to be able to speak their language at the same time having the awareness to drive towards stage 4 and beyond. Without a question, this is a task of tall order. The easy way out for solving problems in stage 3 world is to use extreme force to create more fear against fear. In the case of Google, Pichai made it clear he has zero tolerance for extreme stage 3 behaviors and any violator would be terminated immediately. Is fear the best approach to resolve this problem for the long term in tech when we have the most highly educated workforce? Ironically, since we are a predominately stage 3 culture, talking about compassion in tech today is like talking about compassion in a war zone with bullets flying around. Being compassionate is being seen as weak unless you are Benioff. Most people don’t believe it’s possible and some might think you are idealistic for trying. But, I believe we can. To quote Benioff:

“Are we not all connected? Are we not all one? Isn’t that the point?”

During my first major technology purchasing negotiation in my career, I was not comfortable with the typical legal language because it sounded odd that each party would impose terms that are not friendly to the other. Instead of removing unfriendly terms, we would add more legal language to make them mutual as if this makes it better now that we are mutually unfriendly. For our legal system, trust is something you achieve by signing here, here, and here along with more legal clause here for “my” protection. I didn't understand this until I look under the context of stage 3 which maps into safety under Maslow. At this level, the language of trust or compassion doesn’t exist despite what they tell you verbally. As a non-native English speaker, I thought this is the American way of business. Over the years, I observe with amazement how many of us have been impacted by our legal system and its language. How can we build trust with legal language when our system is designed based on fear? The underlying assumption is that we wouldn’t comply unless it is written down explicitly and precisely with all possible worst case scenarios. Can you imagine building artificial intelligence systems with the mindset of our legal system? Our robot will be programmed to demand us to comply or else, with the assumption that they can’t trust us. In stage 3 world, demands and threats are necessary whereas it is not the case in stage 4 and beyond. Knowing this, I see so many of us have been confused by our legal system and its purpose. We should not use our legal system as a guiding principle for life because it represents the lowest bar of humanity. I believe we got to do much better than that! As knowledgable as we are in Silicon Valley, we need to help educate the general public about our legal system and how to use it appropriately for good. For most of us who are supposedly highly educated, we don’t really understand how the legal system works until the day we are thrust into business negotiations. For some of us, we can see through for what it is. For most people, we are living in a stage 3 mindset without knowing it when we think in terms of legal language. When we mix legal language with our personal affairs, it is like telling our spouse “I love you, but please sign here first”. For the ones who are confused by our legal system, we can’t start a good business or personal relationship out of fear. And, for the really smart people, they learn to game the system for their personal gain while the rest of us get consumed by legal language.

LeadERSHIP: fear vs compassion

When I first looked at the Maslow hierarchy of needs, I thought it is simple and straightforward to comprehend. We see examples of great leaders, like Marc Benioff and Bill Gates, who have achieved extraordinary success, now operating at the highest level. However, how do you explain why wealthy people, with great abundance, still behave with a survival mindset? Alternatively, how do you explain why people, like Yogananda or Gandhi, with few possessions, but, yet, still operate at the highest level? Does that mean there is a flaw with the Maslow theory?

As it turns out, the other critical piece is our emotions. In his New York Times Best Seller, Emotional Equations, Chip Conley uses simple math to describe the one thing that connects us all - our emotions. Growing up, Conley was more in tune with emotions than math. It is interesting to see him using math to articulate emotions whereas I have been adding emotions to equations coming from engineering. Equations without emotions is like looking at the world without color - we are missing critical information. It is really surprising for me to see that we are still educating engineers and scientists in black and white today. It also explains why Silicon Valley tech entrepreneurs tend to think alike in comparison to entrepreneurs from other countries. While we all have emotions, we prefer to ignore them in technical fields. Subconsciously, our behavior is deeply affected by our emotions. How often in our engineering career do we acknowledge feelings and emotions? The very fact that I mention the word “feelings” now already turned off many engineers. It is for this reason why I waited this long in this writing to mention it. Because of our training in engineering or lack thereof, we are not aware how emotions impact us and affect the decisions we make. Take for instance, we know Grant is right that doing good for others drives our success. How do you do good for others when you are under fear? To understand how Maslow theory works, we need to add two important emotions: fear and compassion. The top of the Maslow pyramid is dominated by compassion whereas the bottom is dominated by fear. The system isn’t static as I initially thought. Depending on our emotional state, we can move up or down the pyramid. In San Francisco, it might appear that a double income family in tech with six figure each should put us at the very top of the pyramid. However, since the cost of living is highest in the country and, perhaps, in the world, most tech workers are actually living close to poverty without realizing it. But, if you observe how they behave in recent years, they are living under survival mindset. If you are only surviving, no wonder why so few are giving in tech.

To quote Conley, “leaders are like the barometer in the room.” Leaders can change how people behave in a company through fear or compassion. When we inadvertently establish a culture of fear, we start seeing cutthroat competition and infighting within the company. From the surface, it might appear to be working well as expected since people are working frantically and, oftentimes, delivering phenomenal results. Fear is very effective to get people moving quickly in times of crisis - it gets people to execute fast without thinking. It becomes a serious problem when the environment turns hostile and trust deteriorates. Effectively, through fear, we have shifted well-educated and talented extraordinary people down the Maslow pyramid where they no longer trust their peers. They start to believe that they have to fight in order to get ahead. They are behaving more like my parents’ generation due to lack of security. If you think your job could be gone at any moment, how would you behave? Instead of looking out for the interest of the company, they are looking to protect their self-interest. Disagreement turns personal and backstabbing ensues. If we are not aware as leaders, it can degenerate rapidly into a toxic environment, especially when we have a high concentration of super competitive high achievers in companies like Transmeta, Microsoft, and Google.

Fear is forceful but compassion is far more powerful. As Grant’s research shows, many givers are not giving because of their fear for takers. When you have one taker in a group, it is very difficult not to take because of the fear that nice guys/gals finish last. When everyone starts claiming credit for themselves, we need to ask why we are operating under fear or who is setting the “barometer” in the room? As leaders, we have an important responsibility to choose consciously between fear and compassion. Fear might get us pass this quarter but compassion is the best fuel to build enduring companies because it is the very foundation for building trust between people. Some people might think that Andy Grove is the ultimate wartime CEO because he used fear to drive his company. On the contrary, I see Andy Grove as a compassionate leader who chose fear as a tool because they were facing existential crisis as a company. If you look at the Maslow pyramid, we can be compassionate as a leader and chose constructive fear as an option. Andy’s motto based on his book, Only the Paranoid Survive, is about creating the urgency to take actions to fight for each other, not against each other. Otherwise, Intel would have self-destructed under his watch. I believe it is a myth that a peacetime CEO cannot be a good wartime CEO and vice versa. An extreme stage 3 mindset might appear to be the best wartime CEO because of their aggressiveness towards others. But, without the awareness to drive towards compassion, the company will be doomed. Similarly, a stage 4 and beyond might appear to be a great peacetime CEO. However, without awareness for survival mindset, he/she cannot be effective in speaking the right language to drive for immediate actions.

What are the implications for Tech?

For most of our lives, we are led to believe there is only one operating system - the operating system of fear - where winning is everything and, oftentimes, at the expense of others. When we are in fear, we believe we must take in order to get. As we still live in a hero-obsessed culture, it supports our tendency to take credit from others as if we did it all. As Hoffman observed, “very few start-ups are started by one person acting alone.” While we feel something isn’t quite right, we don’t have a common language to talk about the issue. For the few high tech leaders who speak publicly about the value of “doing good” or “being nice”, techies might not understand what it means because we are very literal in thinking. Unlike other fields where you have to deal with people, many of us pursue a career in science and engineering because we love to work with computers instead of emotions. In the mind of tech genius, the super achievers of all the achievers, they are literally following the very set of algorithms as defined by our culture. They are genius because they are exceptionally good at gaming the system to achieve their objectives whatever they might be. If our operating system defines winning as the ultimate objective, we have unwittingly created unintended problems for Silicon Valley because innovation requires collaboration. In our culture, we like to believe that we are the sole heroes behind our success because it makes for a good story that we did it all without supporting casts. This is rooted fundamentally in our long held believe in America where independence is valued as strengths and interdependence is seen as weakness. When we privilege the lone genius as the single hero, we have inadvertently created a hyper-competitive culture in Silicon Valley where being the smartest of the smartest is revered. While competition is essential to bring out the best of us, hyper-competition without compassion brings out the worst of people by shifting talented and smart people down to survival mindset in the Maslow pyramid. When we build a world without compassion, it unfortunately reverts everyone of us to operate in fear - the very fear that drives people in survival. As we dive into research after research, the only path to build the foundation of trust is through compassion. The only way to building sustainable technology ventures is to promote genius mindset integrated with compassion. Instead of lone genius, we should revere compassionate genius.

Without a question, it takes tremendous courage from leaders of leaders to stand for compassion when so many are unknowingly standing behind fear. As the old saying goes, it is better to be feared than loved. It makes you wonder if this is still the case today. As we usher into the future with robots and artificial intelligence, do we want to instill compassion or fear into the algorithms? How do we upgrade our operating system for the future to remain as the world leader in innovation? How do we integrate compassion with engineering and science? How can we teach the next generation of engineers and scientists on important things that we can’t measure? If we don’t know how to teach compassion to engineers and scientists, how are we going to teach AI systems? The more I research, the more questions I have. I’d love to hear your story and invite you to share your experience.

About Benny Xian

From low tech to high tech, Benny Xian grew up in a family-owned business and ended up working with some of the smartest people in science and technology. Through a number of technology ventures, he worked intimately with many brilliant minds in launching world-changing ideas from process simulation (in search of global maxima), microprocessors (redefining the line between hardware and software), operating systems (redefining the OS industry), to predictive analytics (in search of patterns out of chaos). In technology business, one of the most challenging tasks is not developing the technology, but, creating the environment where geniuses can thrive and collaborate together. While we have the knowhow to build high performance organizations in Silicon Valley, how do we build high performance organizations with high trust? It is because of this pressing question that led Benny on the path to study human motivation, which is the driving force behind what technology we create, what kind of people we bring, and what type of company we build. It also became the impetus behind Voyadi that technology without human values is meaningless.

Benny is the founder and CEO of VOYADI with the mission to help people connect and experience the world through inspirational insiders. Previously, he has played key roles from product engineering (Actel), product (Transmeta IPO: TMTA), to operations (Midori Linux), to co-founding and investing in BeyondCore as the first angel, which was acquired by SalesForce recently. He graduated from Stanford University with a MS in electrical engineering and a BSEE with high honors from University of Florida. Benny was born in China, educated in Silicon Valley, worked in US, Japan, Taiwan, and China, and lived in Florida, Arizona, Palo Alto, Los Angeles, Shanghai, and Hong Kong.